Of the many subcategories of properties that Philosophers have come up with, an important pair are what John Locke named Primary and Secondary Properties (aka Qualities). The distinction between them being that Primary properties are those that are “objective” and “in the object”, while Secondary properties are “subjective” and “in the mind of the perceiver”. Primary properties of an apple would be its mass, shape, size, etc. Secondary properties would be its color, taste, smell, etc.

That apple isn't really red?

Color is a classic case in point because it seems that color might be objective. There are surely some collection of wavelengths of light reflected off an apple that could be classifiable as “red”. Alas, there are mountains of evidence that color perception depends on the person and the external conditions.

A famous mountain of evidence (sorry, pun intended) is Ayer’s Rock (aka Uluru) in Australia which attracts thousands of tourists to see it dramatically change colors right before their eyes. Over the minutes of sunset or sunrise, “the color” ranges thru black, red, pink, orange, brown, etc.

In the rain it even turns blue and purple...

So, the mountain can’t really have a simple “color” property with a simple single value.

Again, as with Essential properties, how is this primary/secondary distinction supposed to make me develop differently than I do now?

- Model Clarity: Keeping the properties of an entity or class limited to primary qualities helps to insure that your data model will match data models developed by others. You will be more likely to agree on what the properties are in the first place, and, on what data type best represents that property (see Stronger Types below).

- Better Normalization: Your entity database tables are normalized when limiting to Primary properties because those truly are properties of that entity. By recognizing and removing Secondary properties, you won’t be mixing in columns that are really a flattened relationship with some other beholder entity.

- Better Keys: When deciding which properties of an entity are candidates for being part of it’s “key” or “identifier”, it definitely helps to verify they are really objective properties of the entity. Otherwise, they are based on some external beholder & conditions that can change over time, even though the entity itself didn’t change! A drivers license search will fail if a witness’ notion of a suspect’s hair-color doesn’t match the DMV’s notion of that hair-color.

- Data Provenance: Realizing that each value of a secondary property begs the question “says who?”, you need to identify the authority that provided each value for that property. As you can see, there could be anything from a one-to-one to a many-to-many relationship between the original class and the various authorities providing data values. If the answer is “all values of this property come from a single source X”, then that need merely be noted in the documentation. At the other end of the spectrum, there may need to be a sophisticated sub-model just to keep track of the source and circumstances of each of the several values that property could take on for a single object! (see the Basel II banking case study below).

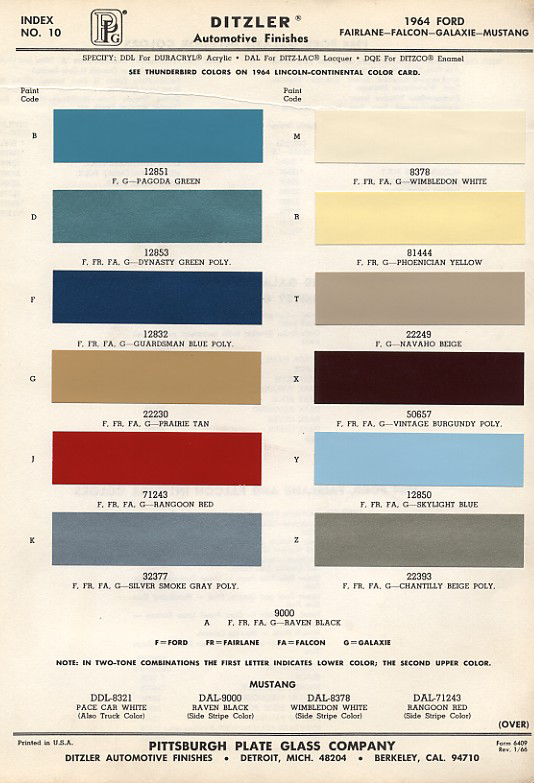

- Stronger Types: Authorities providing data values for secondary properties, usually define entire “types” rather than just values from some universal type. For example, authorities specifying colors usually limit them to a custom collection of colors (i.e. a palette), or even collections of palettes. Ralph Lauren defines many palettes of colors, most with one or more “reds”, but none of them are the same as the “red” of a 1964 Ford Mustang which comes from the small palette of factory colors from Ford for that year. If you need the simplicity of a single universal “red” value then you are looking at defining mappings from one palette to another. Car salesmen do this mapping intuitively by showing you a "cypress pearl"Infiniti when you ask to see either "black" cars, or "green" cars. Do you need that sort of detailed modeling? You do if you are trying to make it easy for customers to find what they want (see the fabric.com case study below).

|

| Ralph Lauren Palette |

Case Study: Basel II Banking Accord

One of the fundamental practices of banks is to keep a certain amount of money in reserve. When taking customer deposits in, and loaning it out to make a profit from the interest charged, there is a danger if all the deposits are handed out as loans. So, a reserve must be kept, but, there is a conflict between larger reserves for more safety and smaller reserves for more profit. Because banks have erred on the side of more profit, over the past several years international banking regulations have added requirements that the amount of reserve be calculated on a more scientific basis, and be optimized over time.

One of the major criteria in determining how much reserve is required, is to base it on the quality of the customers that the bank lends money to, as measured by their credit grades. A credit grade is really just a prediction of how likely a borrower is to pay back a loan, and how much they would leave unpaid if they did default on a loan.

The regulators recognized (though maybe not in these philosophical terms) that “credit grade” is not a primary property of a customer; it is a secondary property based on the grader and the procedure or algorithm used. The Basel II Banking Accord specified that simply keeping track of customer credit grades was not enough. Banks needed to start keeping track of “says who?” and “what did they base it on?”. With this data, it can be verified after the fact which of these predictions of future default panned out. This enables evolving better algorithms and weeding out graders and methods that were not very good.

One of the major criteria in determining how much reserve is required, is to base it on the quality of the customers that the bank lends money to, as measured by their credit grades. A credit grade is really just a prediction of how likely a borrower is to pay back a loan, and how much they would leave unpaid if they did default on a loan.

The regulators recognized (though maybe not in these philosophical terms) that “credit grade” is not a primary property of a customer; it is a secondary property based on the grader and the procedure or algorithm used. The Basel II Banking Accord specified that simply keeping track of customer credit grades was not enough. Banks needed to start keeping track of “says who?” and “what did they base it on?”. With this data, it can be verified after the fact which of these predictions of future default panned out. This enables evolving better algorithms and weeding out graders and methods that were not very good.

Case Study: fabric.com

In the early days of marketing on the web, the start-up fabric.com (since bought by Amazon) was building a web store to sell clearance fabrics and apparel. Like all online retailers, there is the problem of making it easy for the customer to find the products they want. A common approach is to build a web site with a left-column navigation bar containing filter-by-property controls. This works fine for Primary properties, but is more of a problem for Secondary properties.

Alas, if one doesn’t know that there is a difference, one builds all of the filters in the same manner. For fabrics, filtering by the dimensions of the piece being sold is straightforward and effective because it is a primary property. For color however, there are problems because it is a secondary property, and hence opinions differ on how to describe the color.

Look, even though the “color” of a fabric may be in the eye of the beholder, it is an objective fact that the manufacturer described the color as X, right?. How about we use that since we have to pick something?

Well, two big problems:

Alas, if one doesn’t know that there is a difference, one builds all of the filters in the same manner. For fabrics, filtering by the dimensions of the piece being sold is straightforward and effective because it is a primary property. For color however, there are problems because it is a secondary property, and hence opinions differ on how to describe the color.

Look, even though the “color” of a fabric may be in the eye of the beholder, it is an objective fact that the manufacturer described the color as X, right?. How about we use that since we have to pick something?

Well, two big problems:

- All those colorful color descriptions cause an overly large list of colors in the color filter, plus related colors are spread all thru the list (e.g. avocado, green, lime, olive, etc)

- When the customer searches for “green”, she won’t find all those fabrics with the color described as “lime”.

Okay, fine, we are going to have to go to the trouble of mapping each item to a simple set of colors that we pick. So, Mr. Programmer, go set up a set of simple colors in the database so that we can pick the color when we enter these items into inventory. Well, one other big problem:

- While everyone is entitled to their own opinion, some opinions are worth more than others. The programmers did not have the industry experience needed to pick an appropriate set of colors. It was the brick and mortar fabric sellers that knew things like “stripe is a color”! So, it took someone who had experience with what buyers actually ask for to know that along with “green” in the color list, also needed was “green and white stripe” but not the manufacturer’s description “lime and white stripe”. They also knew that, in addition to simple color families like yellow and brown, subtle categories like "gold, “beige”, and “cream” were needed (and in fact the last two combined into a single category). On the other hand the green family did not need to be augmented by “lime” and "avocado" families.